High Performing Startups — Hiring for Values (Segment 3)

Adam Reynolds, Tim Enwall & Matt Butcher

Adam Reynolds, Tim Enwall & Matt Butcher

company

culture

will reed

goals

startup

Refresher

In Segment 1, we introduced you to the overall concepts behind High Performing teams and then in Segment 2, we delved deeper into the importance of founding one’s organization on the strength of core values shared by everyone in the organization. And, in both segments, we spent a good amount of time talking about the core teamwork values essential to High Performing Teams — humility, curiosity, self-awareness, vulnerability, accountability, focus, and passion to name a few.

In this segment, we explore the natural next step after establishing your core values: bringing new team members into the organization who share those values.

Three Legs of the Hiring Stool

When we look to hire a new person, we always look at three core requirements: the strength of their competencies (as it applies to the specific role), the level of competency required for the role, and the sharing of our core values.

Hiring for Level

Our greatest mistakes in hiring have dominantly come from a mismatch in the job level of the person we hired. We underestimated our need for a more senior-level engineer and ended up disappointed in the amount of time we had to allocate to training, remediation, and oversight. This took time and resources that were costly, and in the end, we had to hire someone at a higher level. Parting ways with the entry-level person we just hired wasn’t easy and was draining emotionally for those of us making the decision. We also had to then handle the potential for morale to drop, if even temporarily. We also experienced the opposite: over-estimating the requirements for the job only to see the senior level (4, 5, or 6) employee become bored, frustrated, or unfulfilled with their work which has led to them moving on in situations where we couldn’t provide a more rewarding role.

It has become quite obvious after those experiences how important it is to identify the level required for the role before hiring commences. We could say this is the key to avoiding the trouble we may find ourselves in, however, no matter how many thought cycles you go through, you’ll get it wrong some of the time. And, the more thorough you are in thinking through the short-term and longer-term needs (what will the new hire be required to accomplish) the fewer mistakes will occur. The amount of time and emotional energy saved on each one is much more than you can imagine. Please do as much as you can to assign the proper level to every role.

Start by asking these probing questions of the hiring manager:

- how much autonomy and independent decision-making will this role have (the more autonomy, the higher the level)

- how much supervision is required or anticipated (the more supervision, the lower the level)

- how sophisticated or complicated is the work (the more complex, the more senior the level)

- how vital or single-threaded is the work (the more vital or single-threaded, the more senior)

- is this role actually a leadership role that also requires the individual to do core work (if leading other people and doing work, then we must have a “Player-Coach” (see callout))

💡 “Player-Coaches” are some of the most important and vital people any startup can attract. The definition of a Player-Coach is someone who is passionate about and has the job of leading and managing people ***who also*** has a great deal of experience in the functional area. Player-Coaches are hard to find. When hiring higher level roles, we have found that some candidates feel they are beyond doing the hands-on work and therefore want the role to lean heavily toward managing ***or*** they have all the depth necessary for the hands-on work plus share a desire to lead, however, their leadership passion is driven by ego rather than a servant based approach. Great Player-Coaches can perform when it is time for planning and strategy with the same ease that they can perform daily action ***and they’re passionate about doing both***.

This is one of the primary reasons why, in our experience, “big company” middle managers most frequently fail when brought into early startup organizations: they’re used to the supporting infrastructure that enables them to “just manage” and aren’t used to the execution requirements brought on by under-resourced, young, startup organizations. And, frequently they grow disillusioned because they think they know what a great organization looks like (the big one from whence they came). To them the “emerging process” of a startup would be called “chaos” causing them to believe that they’ve joined a company that doesn’t know what it’s doing, mistaking nascence and chaos for incompetence.

Hiring for Competency

The number one focus in hiring must be skill and talent in the key areas defined for the role at that level. We wouldn’t hire solely based on cultural fit (though we imagine some companies do). An example of culture-only might be hiring a friend, family member, or ex-colleague simply because we like them, want to support them, or know they are loyal to us. While some may do this we don’t operate that way and would not recommend it. Hiring for competency is more difficult. We must be able to clearly define the role and the work/goals to be completed in the present, in the near future, and potentially beyond a year too. We must place a strong emphasis on first understanding the core competencies required for any particular role we’re hiring and then being diligent to find a candidate that is a strong match for those competencies. Competencies are always our starting point and the primary focus for the hiring manager’s initial interview with prospective candidates. The job description and job posting are therefore critical to finding the right person.

Hiring for Values

Over the course of three startups (Revolv, Misty Robotics, and Fermyon) we’ve both perfected the art of hiring for values and become convinced that it underpins every important aspect of a high-performing team. Why? Because values are foundational to the development of a high-performance culture, as we covered in Segment 2, which drives alignment in the day-to-day operations of the organization. And, values are the drivers of attention, focus, action, communication, and collaboration because in many ways “our values make us who we are.” When our work environment aligns with our values we, as workers, can be ourselves. Being true to ourselves has a huge benefit, it creates fewer moments of friction, increases the joy we derive from our surroundings, increases our productivity, and enables our focus to be on our contribution to the organizational goals.

When we couple hiring for values with the values of a High Performing Culture we get what we’re driving towards: the fundamental makeup of a High Performing Team.

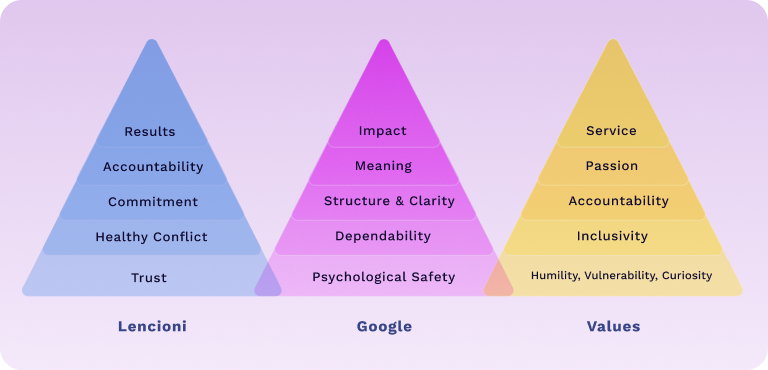

💡 A side note on both Lencioni and Google frameworks: neither of them spends much time on what’s beneath Trust and Psychological Safety - they both basically assume that you start there. I.e. “assume your environment is trusting and psychologically safe and then build these additional capabilities on top.” In our experience, the foundational characteristic is: a desire and ability to build meaningful relationships with one’s colleagues. The most essential ability here is emotional intelligence (some level of each of these: self-awareness, managing one’s emotions, social awareness, and relationship management). So, in addition to looking for your company’s Core Values as you hire, we highly recommend screening for moderate to high emotional intelligence (depending on role) and a moderate to high desire to create meaningful relationships.

Hiring Essentials

Before executing the process of hiring it’s essential to get two things written down and agreed to by the appropriate members of the leadership team: the Role Description and the Interview Team.

Role Profiles

Role Profiles are a superset of the public facing Job Description coupled with more behind-the-scenes information about the role such as:

- Rationale: Why are we hiring this full-time (or part-time) role and, thus, making this long-term financial decision? How does it fit into our strategy? Why is it vital this role be an employee vs a contractor (either temporarily or semi-permanently)?

- Level: We answer the questions above in our “Hiring for Level” document to determine whether we’re hiring an entry-level individual contributor, a senior-level individual contributor, a team leader, a manager, or an executive.

- Measures & Decisions: what do we expect to be the core measures of what excellence for this role looks like? What decisions (see: DRIVIT) are we explicitly anticipating delegating to this role versus the decisions still reserved for the hiring manager or other leaders?

- Salary associated with this Level: looking at comparable market salaries for the role or comparable salaries that already exist internally in the company for this same Level, identifying what we feel comfortable paying. (Note that in the US there are many states, as of 2023, that require companies to disclose the salary range in the job posting).

- The rest of the job description: description, responsibilities, requirements, desires, and results.

To see this in action check out Reference [4], Fermyon Internal Role Profile Template.

Once a Role Profile is complete it’s also essential to iteratively work the Role Profile with the recruiter / screener (see process below) such that the screener has as clear a picture as possible to narrow down the applicant pool. Feedback between hiring manager and screener is essential.

Interview Team

As we head into the hiring process, it is imperative to be clear about who the decision-maker is (usually the Hiring Manager, with a veto from Human Performance, as detailed below), who the key players providing input are (this may include essential peers or cross-functional employees), and, if we’re hiring a manager, potentially some or all of the team-to-be-managed. If we’re involving a recruiter (whether on a contract basis or as a member of the team), we must ensure that the recruiter is fully briefed on what we’re looking for in viable candidates. Typically, there is also a hiring coordinator who manages logistics between the Interview Team and the candidate.

If you want more depth on our hiring process, including role definitions and the use of information systems, check out Reference [5], Fermyon FIP004 Hiring Process.

Deep Dive: Hiring for Values

Many companies are including culture interviews in their hiring process. There is a large variety of ways these interviews are conducted and the responsibility of those interviews falls to a fairly broad group. For more than half of the companies we’ve asked, the culture interview comes towards the end of the interview process after a candidate has been well vetted for all the role criteria and is a top candidate. At Fermyon (and a previous company), we put the culture interview right after the initial screening of candidates. We believe that hiring for culture fit is equally or more important than job skill fit. That doesn’t mean we would hire a candidate on the merit of their culture interview only, just that we prioritize culture fit more highly than most. And, it makes me wonder, if the culture interview comes last in the process, what happens to a candidate who has nailed all the role responsibilities but doesn’t appear to be a culture fit? Does the hiring team then reject the candidate? It sounds very painful to take the time to do all the interviews only to find a mismatch in culture. Because that seems so ludicrous, it has to be that the culture fit isn’t as highly valued as skill/experience fit and therefore the culture considerations get minimized or overlooked altogether in the end. It is important in your company to know how culture fits into the hierarchy of priority when hiring a candidate. We all have heard stories about a top performer (perhaps a SME) who produces sales or builds software being given leniency relative to their unflattering cultural behaviors. That can be very destructive to a team when that happens.

At Fermyon, the Head of Human Performance (who conducts most culture interviews) has veto power simply based on culture fit. This ensures that a candidate that moves forward in the hiring process has already been approved for culture, thus allowing the remainder of the team’s interviews to focus on skills, experience, aptitude, and knowledge. This is just one of the many ways a company culture can be maintained as the company grows in size. If a company can maintain this level of rigor throughout their hiring future, they are more likely to have less conflict due to values clashes. If a veto of a candidate occurs, this saves the candidate and the rest of the hiring team from hours of scheduling and interviewing.

A culture interview designed to discover how the candidate thinks about and acts on specific values can be accomplished in many ways. The process for building a solid interview begins with knowing what you want to find out. As a developer of several approaches to the culture interview, I start by asking myself, “how would I know this candidate is a strong fit, adequate fit, slightly questionable fit, or definitely not a fit?” My feedback on each candidate is critical to the hiring manager. They must rely on my assessment of culture fit and blend that with the strength of the candidate on all the other important criterion. In addition I absolutely I must be clear on what it looks and sounds like when the candidate is not a fit, so that I can justify my veto to the hiring manager. It is imperative to use my veto only when it is clear to me, and then I have to be specific in providing my reasoning. During the interview I take my time to write down all the words, phrases, and emotional expressions that I hear or observe that reveal the beliefs and values of each candidate.

I spend time to define the values that our company cares most deeply about. Then I capture how to recognize those values if a candidate truly embodies them. I create questions that enables the candidate to explore the values. This allows the candidate space for them to both interpret the values and share examples from their past of the values in action. I also want to hear what they’ve seen happen when one or more of the values are not being demonstrated, like arrogance in a culture vs humility or exclusion vs inclusion.

A few simple examples of my approach:

- If I care about how candidates build teams or think about collaboration, I listen for “we” in their language when they describe their accomplishments. That isn’t to say I don’t want to hear “I”, that is important too. I want to know what they contributed, drove, or created, and I want to hear them give credit to those around them who made a difference too. Ex. “I created the sales strategy for project X with input from my team. Then, we implemented the strategy, and I made sure everyone kept their focus. After a few adjustments to the strategy, we drove a 30% increase in sales from the previous quarter.”

- If I want to assess curiosity, I note the candidate’s questions of me and follow-ups. I pay special attention to their stories about how curiosity contributed to the success of an initiative. How a candidate describes the value of curiosity to the creative process or to course correcting or to any high-performance activity will give me a sense of how this value lives within the candidate.

- For honesty, I ask for examples when the candidate was challenged by an issue with integrity. I want to see how they tell the truth, how they ask for the truth from others, or how dishonesty showed up in their past and what they did about it. Perhaps they will share some feedback they gave someone which demonstrates their willingness to share something potentially difficult to hear. Humans hold back sometimes or turn away from situations of discomfort, that is a part of being honest about what is happening and taking the initiative to say what they think is true.

- Learning about humility puts my attention on the credit the candidate gives to their team members in creating successful outcomes. Most of us know what we know because of those who came before us and from our own drive to learn. Giving credit or sharing the process that enabled our success is often a humble approach. Rarely does anyone do everything on their own. I don’t expect self-deprecating language, I want candidates to own their contributions, and at the same time have humility too.

- I want to know how versed the candidate is with diversity, equity, and inclusion. I ask for the make-up of their previous teams, and then explore what inclusivity looks like to them in daily practice. Exploring equity, I might ask if they have ever created an accommodation for someone, and, to describe how that worked. There are many values that could be assessed in a culture interview. The bottom line is to ensure you have crafted questions that will cause the candidate to explore their past through the lenses of values. Pay more attention to the values you care about most. And finally, know what you are watching and listening for.

Hiring Process Lessons Learned

Over the course of our careers we’ve hired more than a hundred people using our High Performing Team philosophies and we’ve learned a great deal about an effective hiring process.

Come from one’s values

Time after time those who have been hired rave about our interview process because it’s authentic and conveys our foundational values. In Fermyon’s case we’re humble, curious, inclusive and passionate about what we do and it shows. Interviewees have said they can sense our authenticity and feel comfortable in their interviews. We exhibit those top four values which becomes the interviewee’s first exposure to them — and they will either find themselves subconsciously aligning and moving toward the organization or subconsciously misaligning with those values and moving away. This is precisely what we want. A fit must be experienced on both sides.

Move with intention and alacrity

Hiring processes that lag convey a few subtle messages to interviewees:

- we don’t really care about filling this role

- we don’t really care about you (the candidate)

- we don’t really know what we’re doing

Once you’ve committed to the spending associated with a full-time employee and posted a job then it’s more than likely your business has a clear need. Fill it; don’t dawdle. And, if you find the overall process is dragging out (because of candidate flow, internal distractions, or priorities) then please at least move the candidate through with velocity and over-communicate, authentically **with those who are stalling. Even if the process is moving along swiftly, over-communicate about where they are in the process, what they can expect from the next step, when the next step will happen, what’s happening with their overall candidacy, what the overall timeline looks like, etc.

Effective Sequencing

The hiring process can be an extremely challenging and frustrating process because a) it’s so critical and so foundational to everything that lies ahead for the organization, b) communicates so little information about the candidate in the process, and c) can consume a lot of time if one allows it to.

It doesn’t need to consume a lot of time from key resources who are focused on executing the current business. Yes, it will consume some significant amount of time from the hiring manager, but if one sequences the process properly even the hiring manager’s time can be saved in the overall process.

The sequence should be pictured as a funnel — the vast majority of candidates come into the top of the funnel and are:

- Screened by a more generally available screener (usually a recruiter or hiring coordinator) - moving from hundreds to a dozen or so applicants.

- Then screened for competency by the hiring manager - moving from a dozen to a handful.

- Then for culture fit by the values interviewer - moving from a handful to a few.

- if hiring a manager, then a manager screen is key.

- And then, and only then is the broader team brought into the process.

- And finally, the CEO (optional).

The lion’s share of our high-priority interviewing resources are applied to only the final few candidates.

The Role Profile is essential to the initial screening process. Without a good Role Profile that general-purpose resource doesn’t have the necessary information to review resumes and have screening conversations to narrow the applicant pool down. Early in the process rapid back-and-forth communication between screener and hiring manager is critical to enable the screener to be effective and efficient (Screener: ”what do you think about candidate X’ resume”? Hiring Manager: “They lack competency x; and that’s a vital competency”. Screener: “Oh, that’s helpful - I can rule out a bunch of other candidates then.”) Additionally, a Role Profile can also be used by the hiring manager and initial screener to develop a screening questionnaire that creates a far more efficient process.

The importance of a veto

Hiring managers have powerful incentives to get a person into a role — usually because the role has been identified on the back of work that is either not getting done or work that is overwhelming other employees.

💡 Tim wrote an entire piece titled “Enwall’s Principle of Hiring” about these incentives and how to think about balancing the incentives with practical necessities while staying true to the mandate to get only the best, right person into the actual full-time employee seat. See: [https://medium.com/tenwalls-views/on-leadership-enwalls-principle-of-hiring-95c5ea2f7d3a](https://medium.com/tenwalls-views/on-leadership-enwalls-principle-of-hiring-95c5ea2f7d3a)

Additionally, hiring managers are not usually well-versed in the soft skills required to evaluate a candidate’s fit with the values we’ve established.

Because of the incentives and the lack of skilled competency in discovering values matches and mismatches we have found that it’s a best practice to let the Human Performance function have a veto over all hires. (See Tim’s post on DRIVIT for more on vetos.)

The word veto can have powerful connotations. In the hiring process case it simply means that values trump competencies when it comes to the actual, final hiring decision. No matter how competent, skilled, or expert a person seems, an organization is asking for a great deal of pain if it hires a person over the objections of the values interviewer. We’ve learned by painful experience to just not do it. So, in our organization, even if the hiring manager is laser-focused on a “Yes” decision for candidate X, they don’t get a job without a corresponding “Yes” from Human Performance (or an over-riding Tie Breaker from the CEO - again, see DRIVIT).

Systematize and Measure What Matters

Long ago we learned that, especially when we’re in a period of hiring that involves more than one role, having an Applicant Tracking System is worth its weight in gold as it coordinates all parties, keeps candidates informed, speeds the process in many cases (i.e. competency questionnaires), and enables measurement (see below).

We have always believed in “measuring what matters” in all aspects of our business and for hiring we picked up this Best Practice from our investor, Amplify [1] — to measure our hiring process, especially when we’re in a hiring sprint. The three essential measures are:

- Outreach to Interest ratio. This only applies when using an explicit outbound recruitment resource and measures the number of candidates to whom the recruiter has reached out to the number of candidates expressing interest in the role - as evidenced by getting to a Hiring Manager screening interview. A great ratio is 3-5%; a “meh” ratio is 1.5-3%

- Final-Round to Offer ratio. This is the ratio of people who make it past the values screen and receive an offer from the company. A great ratio is 80%; “meh” is 60-79%

- Offer to Close ratio. This ratio speaks for itself — how many candidates who receive an offer from us accept the offer. Great is, again, 80% and “meh” is below 80%.

We highly recommend listening to Natasha’s podcast [1] as it does an excellent job of describing the “why” behind these three numbers.

Signing the Values Statement

Most companies only have their onboarding employees sign the offer letter and a legal agreement surrounding confidentiality and intellectual property. For three companies now, we’ve also had each employee sign our Values Statement [3]. Why? Because it:

- outlines what they can and should expect (and should expect to hold leadership accountable to)

- communicates how vitally important these values are

- describes their ongoing role in making these values an integral part of the organization

- is a signed agreement we can revert back to in cases of conflict

Onboarding Matters!

As we wrap up this Segment 3 on Hiring, we would be remiss if we didn’t talk about the importance of what comes next: the actual onboarding of the employee into your organization. The first 90 days of any new employee’s journey with your organization are important in so many ways — these 90 days set the tone, establish precedent, educate the employee about a vast number of topics, create the basis of collaboration and teamwork, and establish whether the new employee is actually a good fit for the role. As much as we want every hire to have been a great decision, we recognize that sometimes we make mistakes — so we don’t want to compound that mistake by having a poor fit consume more of our time and resources while creating friction and distraction for the rest of the team; we want to move on quickly!

In our onboarding process, we’ve got logistical and system(s) introductions, processes and policies, collaborators, strengths explorations (the subject of Segment 4!), executive check-ins and more.

For an in-depth dive into what our onboarding process map looks like check out Reference [2], Onboarding at Fermyon

Summary

In Segment 2, we outlined why Company Values were such an important document and organizational understanding to create at the outset of the organization. This document establishes a foundational structure against which we need to execute. This Segment 3 describes the practical realities of executing the hiring process, especially as it relates to finding employees who embody and model the Company Values you’ve established. When every employee’s values align with the company’s values, the fundamental building blocks for harmony and magic ensue. The basic building block for High Performing Teams is established when the hiring process prioritizes all of the essential values of teamwork.

Segment 4

Coming Soon: High Performing Startups: Transparency, Authentic Expression and StrengthsFinder (Segment 4)

References

- See Natasha Katoni’s Podcast notes at: https://amplifypartners.com/company-building/recruiting-metrics/

- Fermyon Onboarding Template (PDF of a Notion database so excuse the ugliness)

- Fermyon Values Agreement

- Fermyon Role Template

- Fermyon FIP004 Hiring Process