High Performing Startups — Founding Values (Segment 2)

Adam Reynolds, Tim Enwall & Matt Butcher

Adam Reynolds, Tim Enwall & Matt Butcher

company

culture

will reed

goals

startup

Refresher

In Segment 1 we introduced you to the overall concepts behind High Performing teams, some background about the authors and the highest level outline of this practical guide to building High Performing teams.

In this Segment we talk about the most essential effort that must occur before you coalesce your founding team or hire your first person. If you’ve already coalesced your founding team, stop immediately, do this exercise and be prepared for the potential that the exercise might change the makeup of this founding team.

Before you begin, an in-depth introduction to Trust and Psychological Safety

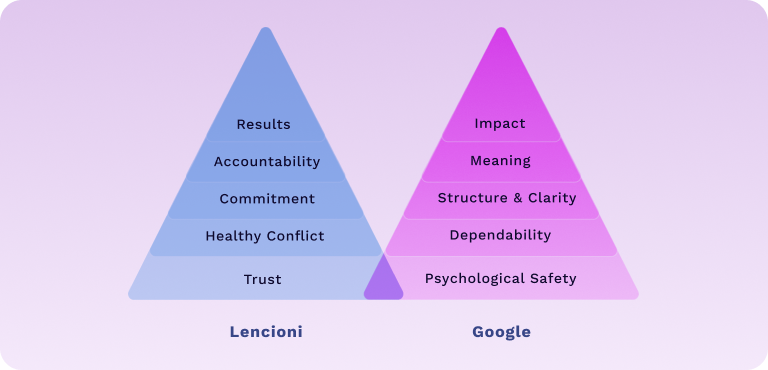

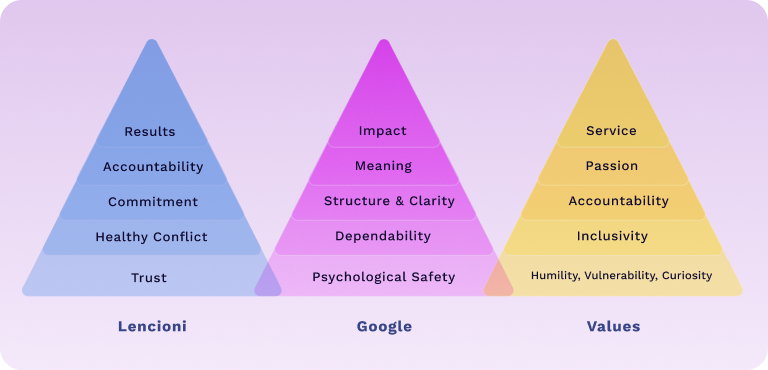

At the base of Lencioni’s and Project Aristotle’s triangle(s) defining high performing teams [4] is the concept of trust and psychological safety. It’s analogous to Maslo’s hierarchy of needs where, unless the first, foundational need is met it’s very difficult to meet the needs of the higher-order concepts. Everything about High Performing teams relies on the ability to create Trust and Psychological Safety! If one cannot create this core requirement one cannot have a High Performing team.

Trust and psychological safety are often mentioned together, however, in our view they are distinct. And highly related.

Trust is something that is earned and deepened over time. You could say that many people give trust at a lower level in new relationships freely. Then it becomes earned as it is deepened. That initial type of trust is typically at a level of 1 or 2 on a scale to 10.

Psychological safety on the other hand is not earned, it is provided. Each of us is responsible for creating an environment where those we work with feel safe with us. Safe to speak up freely with their opinions, ideas, and feedback. Safe to ask questions without condescension. Safe to work independently. Safe to challenge a decision or a position. Safe to be curious. Safe to be our authentic selves. In this section we’ll define trust and psychological safety to create a shared understanding when those terms are being used throughout this segment (and into future segments).

Trust

What kind of trust are we talking about? There is an “overall” trust, which can be defined in many ways, from trusting someone to put in a lot of effort, to lifting you up in tough times. If we were to think of someone in our lives that we trust deeply and then ask ourselves “what do I trust that person to do?” The list would probably be long and encompass some very significant items. We might say, “trust them to have my back” and “trust them to give me support in difficult times of need” and “trust them to be honest with me” or even “trust them with my life.” This kind of trust can be created in business, but it is rare and often occurs with people who work together for many years and who have gone through very challenging times together. Of course, you might work with your best friend, mom, dad, siblings, or children and have that kind trust with them.

A subset of that more encompassing version of trust is “counting on” trust. We might even say that counting on someone is a building block for developing trust. There are very basic ways we count on each other. In the case of partnering on a project with a colleague, we might subconsciously ask ourselves, “will my colleague complete their tasks which unlock my ability to complete mine?” (i.e. are they, from Lencioni committed and Accountable; or from Google dependable?) Or something even more basic, can I count on my colleagues to show up on time to meetings? We unknowingly count on our colleagues to do many things and if the ones we feel strongly about don’t happen, we realize we can’t count on someone, which often slows or even halts the process of deepening trust and building a solid relationship.

The more types of things we do for others or types of things we demonstrate in meetings or in written communication the more our colleagues get to know what they can expect from us. If we always ask for and acknowledge opinions from our colleagues we can be counted on to do that. The more we show up on time, voice our opinions with humility, provide caring and direct feedback, listen and acknowledge what was said by someone else, be patient, be passionate about our work, and deliver the results we signed up for, the more our colleagues can count on any and all of those things from us. The reverse is also true. If we are always late, interrupt others, keep to ourselves, hold in feedback, disregard others’ ideas, be impatient, talk behind other’s backs, and fall short of our deliverables others will withdraw from us. They will learn that they can’t count on us for the things that are most valued in business. They will count on us to be a way they don’t want to engage with. If we are to build team cohesion, the first list is what we want to create. We want others to enjoy working with us and to count on us to be a solid member of the team.

The development of the bigger, deeper trust takes time and consistency. Trusting someone to represent our view in a meeting takes a level of consistent understanding. That kind of trust says, I know my colleague understands me and my view so well that they will reflect my thinking. If someone sticks up for us in a difficult moment our level of trust for that person deepens. If someone talks us through a difficult situation at work or at home (if we are willing to be open) our trust deepens. Typically it takes more courage and often vulnerability to go past simply counting on colleagues to truly trusting them at a much deeper level.

Psychological Safety

What dictates whether or not your team thrives in a healthy culture is a manager’s ability to create psychologically safe conditions for the people they work with.

LeaderFactor [5]

Psychological safety begins with managers and leaders, as the quote above speaks to, but it certainly doesn’t end there. All employees have a responsibility to each other to provide a level of safety that allows for great collaboration and open feedback. Easier said than done, most humans being somewhat fragile in their ability to receive feedback. However, the more the culture engages in providing feedback the better it gets at both giving it and receiving it.

What is Psychological Safety?

A psychological safe culture is one that has given each employee permission to contribute while knowing they will be heard and their contribution considered respectfully. Many employees have the desire to bring up concerns, disagree openly, and provide feedback. If a safe environment to do so has not been provided, the individual, the team, and the organization will suffer as a result. In addition, employees want their questions to be received and acknowledged even when the answer may not be satisfying.

Here are four distinct ways to understand psychological safety:

- The need to connect and belong - Be Included

- The need to have a voice - Challenge, Inquire, Give Feedback

- The need to grow and learn - Explore, Ask, Discuss

- The need to work independently - Focus, Contribute, Produce

Psychological Safety and Courage

Take a moment to consider this question: How much courage does it take to speak up in a psychologically safe environment?

Answer: None

For many of us, it does take courage to provide someone feedback. However, that courage is typically dependent on how much fear we have in providing the feedback. If we know the recipient will be open and explore the feedback with us, the fear will likely be minimal or non-existent. Without fear, courage becomes unnecessary.

The overall goal of psychological safety is to create an environment where courage to speak up is unnecessary. Where the fear of retribution or defensiveness is non-existent. It is also to create a feeling of safety such that ideas flow, creativity is embraced, conflict is addressed, and leadership is encouraged and developed. Where results are pursued with vigor and with the absence of friction or turmoil.

In this kind of environment, all courage to take risks in a workplace would be to achieve job-related growth, not due to a lack of safety. In other words, why would anyone have psychological safety fear when it is safe?

Ex. “I’m going to give my opinion about the direction this company is going that may not be popular, however, I feel it is critical to consider.” A group of peers might consider that opinion ill-informed or unfounded, but in a psychologically safe environment, no one hearing it would feel threatened and therefore have a need to defend or retaliate. Therefore the courage is related to speaking an opinion that may not be favorable to others and may put the person taking the risk to share it at odds with the group. The opinion could also be considered wise, important, and critical to consider, which is the reason to have the courage to share it in the first place.

Psychologically safe: The person providing the opinion could be considered brave to bring it up.

Not safe: The person could be labeled not a team player which could lead to non-inclusive behavior, or worse.

Creating Shared Values

The desire to create a psychologically safe environment or to build trusting relationships requires a commitment to both as core company values. These two among many other values will be the drivers of activity and decision making within an organization. That is why it is key to discuss values and find as many shared values as possible when starting a business. It is also critical to uncover the core values that will be in conflict and to discuss how to resolve those conflicts. (See Shared Values Exercise below)

Background - Core Values

Our personal core values have been inherently ingrained in us since early childhood by our families and the environment. They come from the life lessons we’re taught and repeated over time. Our values act as filters and determine people to whom we’re drawn and those to whom we’re not. As one might imagine, with over 8 billion humans on the planet, one’s individual core values will be similar or vastly different from another’s core values. Our values determine what we think is important and equally what isn’t. They are at the root of what we pay attention to and therefore how we behave.

In business we have seen entire companies ripped apart because of a schism in core values. One founder is a spendthrift (spend to grow) while the other founder is miserly (save to last). One founder is hyper competitive (I need to be the best) while the other founder is focused on collaboration (we win together). One founder has questionable ethics (the ends justify the means) while another founder has strict ethics (principles first). One founder is a rule follower (rules keep order) while the other is a rule-bender (rules are flexible). To name just a few.

Examples of values you can find within businesses are:

- Honesty;

- Trust;

- Integrity;

- Accountability;

- Commitment;

- Achievement;

- Success;

- Service;

- Growth;

- Excellence;

- Curiosity;

- Transparency;

- Collaboration;

- Passion;

- Openness;

- Inclusivity;

- Diversity;

- Equality;

- Support;

- Learning;

- Balance;

- Input;

- Effort;

- Self-awareness;

- Humility;

- Caring;

- Competition;

- Kindness;

- Communication;

- Effectiveness;

- Efficiency;

- Speaking up;

- Acknowledgement;

- High performance;

- Wellness;

- Risk-taking

- Equity;

- and hundreds more…

Each of these values can be defined by behavior. As a consultant I, Adam, often see posters on walls of businesses with sayings or lists of values the company defines themselves by. When I have asked employees if those values are alive and well within the culture, they often pause to look at the poster, then take a moment to think, then typically they answer “sometimes.” If a value is part of the culture you’ll see it in behavior. People being honest with each other, providing feedback that is clear and kind. Bosses sharing what is happening at the highest levels in the business (transparency). Marketing materials that demonstrate how their company is better than another (competition). Metrics that show the effectiveness of the sales and marketing motion. Customer Success departments who have a high customer health score (service) or NPS (excellence). Managers that weight diversity heavily in their hiring practices. PTO policies that embrace work/life balance as a guiding concept. If you want to measure the health of your culture, ask about the values you care about and ensure they are being demonstrated throughout the businesses’ practices.

Starting a company together is probably one of the most pivotal moments in each founder’s life, (especially if it’s their first business). This is why it is critical to start that journey with cohesion, with as little friction as possible, with an all-for-one / one-for-all belief in each other and the vision/mission. It is often a multi-year commitment and in some cases it becomes decades-long. In rare cases it could even last for the rest of one’s life. These kinds of commitments have been compared to that of a marriage. The scope and intensity of the work together can be a driver for founders to spend more of their time together devoted to the business than they will with their life partner. It is because of this level and duration of commitment, and the profundity of the commitment that makes shared values extremely critical. Anyone who has witnessed life partners dissolve their relationship or have experienced it first hand due to “irreconcilable differences” knows what we’re talking about — it can be the core values central to each partners’ identity where they experience a mismatch. That at some point in the relationship their values move them apart. If you spend enough time around startups and founders, and dig into the specifics of the data on the ones with early failures, more often than not you will uncover one or more values that cause those irreconcilable differences.

Most co-founders spend a lot of time making sure there is synchronicity of experience, blending of strengths, passion for the mission, and that they have a shared desire to take a risk together. All of those are important aspects of the founder partnership experience. So, to go forward to create a new business with any of these at odds is to beg commitments made and later broken, heartache, anxious nights, racing hearts, anguish, too much drama, disappointed stakeholders, and often multi-year lawsuits. Do the work on the front end, and get started aligned.

“If there is one thing, and one thing only that I would wish upon every founding pair, group or team: that they do a shared values exercise and only move forward with those founders who share the top core values identified together. Many other aspects of company building and managing can be vastly different than in these segments, but the one common denominator that must exist, without fail, is shared values. Otherwise the probabilities of implosion - either early, when only a few other stakeholders are collateral damage or late, when potentially hundreds of thousands of stakeholders can become collateral damage - are just gigantically high.” Tim Enwall

Physiological Impacts of Inharmonic Core Values

Further motivation to spend time on shared values is related to the impacts on our physical health when our values clash with other’s values. Much has been written about the profound health impacts of too much cortisol. Chemically speaking, when we encounter an experience with another person who is behaving from a dramatically differing set of core values than our own, we experience a hit of cortisol. Cortisol is a steroid hormone that is produced by your two adrenal glands, which sit on top of each kidney. When you are stressed, increased cortisol is released into your bloodstream. Having the right cortisol balance is essential for your health, and producing too much or too little cortisol can cause health problems. Conversely, when our core values are in sync (with friends, life partners, or colleagues) we experience increased levels of serotonin and oxytocin (as written about extensively in Leaders Eat Last [5]), both chemicals infuse joy within us. Science has shown us there are real positive physiological impacts of having shared core values.

What about conflicting values?

When it comes to agreeing on a set of core company values, conflicting values will emerge. Not all conflicting values need to be addressed. However, if there are significant differences in values that will be utilized to drive organizational decision making, they must be discussed. In many cases, people can find ways to address and resolve their conflicting values. However, if left unspoken, they can pull people and businesses apart. We will cover conflict in upcoming segments of this series as healthy conflict is another vital element of High Performing teams.

How could core values enhance or conflict with modern diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts?

Some might argue that vastly different people, with different lived experiences, within diverse cultures will inherently have vastly different sets of core values. And, yet, many core values are shared by people across thousands of different lived experiences and countries. For example many people of different cultures across the globe are humanitarians. They agree that the principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence are fundamental to humanitarian action. They may differ in many other ways, but share these core values.

Diversity, equity and inclusion efforts don’t mandate that “thou shalt bring anyone and everyone into a cohesive effort to achieve a specific mission”. Instead, they concentrate on the open-hearted, equalized welcoming of a subset of people with vastly different lived experiences who, collectively, are passionate about achieving the mission and share a common set of values.

In other words, there are many, many people to welcome into a company, with thousands of different lived experiences each of whom, share the same core values.

It’s been our experience that beliefs and values can get confused or conflated. We don’t want anyone thinking that having shared values is the same as shared beliefs. In diversity research we see over and over again that having differing points of view is healthy for a team or organization. One form of a “point of view” is a belief. Therefore, having differing beliefs will often be of service to success. Too many shared beliefs can create rigid thinking and teams can get stuck and struggle to find alternative pathways to challenging situations.

A belief is a generalized assumption about the world. They operate in a similar way to values in that they influence our decisions and behaviors. However, they often inform our values. The belief “I learn quickly” contains the value of learning within it. Someone who believes they learn quickly likely values learning. And not everyone has to believe they learn quickly in order to share the value of learning. Someone who values support or help may have a belief “There’s no one to help me” or “I can’t ask for help because it means I am not smart.” In this case, we would say those two beliefs are limiting. Beliefs can be both empowering and limiting depending on what they enable or hinder. Believing that people are unreliable could create a tremendous attribute of self-sufficiency in a person, which most of us would say is empowering. However, believing that same thing about people could create distrust, micromanaging, lack of collaboration, poor communication, and a variety of other behaviors that we would say are limiting.

Shared values will align an organization around who they aspire to be. Ex 1: “We are a courageous, curious, mindful, success oriented organization.” While this statement of corporate identity is very amorphous, we can all imagine the behaviors we might see in an organization who claims these values. Ex 2: “We will lead the world in conservation by the end of 2025.” This is a belief that says a bit about who the company is and what they aspire to be, but the phrase doesn’t explicitly say what they value, but rather what they will do. And, reading between the lines, we can imagine what a few of their values might be (conservation, leading, catalyzing, innovating).

Values are drivers of importance and often connected with who we are. Once established they rarely change over time. Whereas beliefs can be more temporal and can shift, sometimes frequently. This, too, is where diversity, equity and inclusion efforts can shine — by bringing in people with vastly different lived experiences who, in turn, have vastly different beliefs while holding the same core values. Those beliefs will create the crucible of healthy debate, creativity, and inspiration while not being so inherently ingrained as to be immovable and non-malleable. The shared values will provide the ultimate umbrella for cohesion.

The Shared Values Exercise

Every founding team should perform this exercise as early in the development of the startup as possible.

What medium you use to do the exercise (via sticky notes, verbally, or in writing) is far less important than the exercise itself.

- Start by capturing the values you believe to be the most critical to running a business. Don’t worry about the order of importance. The list could be as short as 4 or as long as 15.

- Perform a stack rank exercise of your Top 10 core values. Many people are familiar with stack-rank exercises, however, this one has a slight twist.

- Put them in the order of importance for you.

- Then, starting at the top, ask yourself this question: “Is #1 the most important thing about building a business?” If the answer is “no”, ask which value is the most important, and then move that one to the top.

- The next question, while unrealistic, is necessary to get a solid stack ranking. “If you could have #1 but not #2, would that be okay with you?” Force the question as an absolute, you have to choose one or the other. This causes the hierarchy of values to become clear. If the answer is “yes,” move on down the list. If the answer is “no” switch the order and ask the same question again.

- Repeat this for as many values as you want.

- Once complete, look back over your list and make note of how important the top 4-5 are for you.

- Compare your list with the list(s) of your co-founders. Notice where their is strong alignment within the top 4-5. These are what matter most to you.

- If you find a big difference in the top 4-5, this is a warning flag to be explored. You may find that your #2 is their #6 and their #1 is your #9. Or someone may have a value that isn’t listed on anyone else’s. Discuss these differences. All people think about business success in different ways and sometimes a founder may have been thinking very big and into the future and another was thinking about the business within the next year. Figure out if there are simply fundamental differences in how you each would build a team and culture. It may be that going into business together is unwise.

- As you continue down the list, note that each value holds less and less importance. Any values out of your top 10 and others’ top 10 are not likely to lead to big trouble.

- Then, collectively, come up with your company’s top three to five Like every joint decision, this might take massaging and a bit of of wordsmithing. Note: some core values are adjacent to other core values and/or one word may resonate more and be more important to one of the founders than another. The final decision on the list must have whole team alignment.

This exercise will be in service of the company you want to build. And it may be enduring throughout the existence of the company. Of course, some tectonic shift in the company’s trajectory could occur which would beget revisiting the core values. The fact that you spent some quality time constructing the company’s core values warrants broadcasting them. The values could end up on your walls or virtual walls, your website, your job solicitations, and used within your interviewing process for employees, contractors, or even board members.

Create the document that shares these values, then communicate what the behaviors are that demonstrate the core values you’re talking about. Describe them in detail. Then, share them with each person who joins your mission as an employee and have them sign that they a) understand those values and b) are committed to upholding them (see 1 for Fermyon’s example of this document). This step merely cements both the importance of these shared values to everyone while also creating the basis of the commitment to uphold and model them, which you may find yourself having to return to in the future: “you committed to these values and to the principles in this document”.

What if we’ve already started our business or our business has been operating for quite some time?

It’s never too late to do this exercise and, in our experience, unwise not to do so. If you’re taking over a new group, do the exercise. If you’re experiencing some cultural upheaval, do the exercise. If you’re humming along reasonably well, do the exercise. If for no other reason than you can bring clarity to everyone inside the company and any new employee. The changing of the CEO might be another reason to do the exercise. Be cognizant of the need to pause and reevaluate core values.

💡 If you do this exercise after a group has been established and operating for some reasonable period it is highly probable you will find people who are not aligned. In other words, had they been a potential co-founder on Day One, you would have done the exercise, realized there were irreconcilable differences and, no matter how attractive the rest of the partnership looked, decided not to move forward because of the future pain you are avoiding. Expect that there will be these misalignments. If it happens that any of the key core values (1-3) are missing from anyone’s top 10 list, then you will need to acknowledge the mismatch and find a way to manage parting ways. If the leader (CEO) has a top value that is not in the top 10 of the group, then it might take some courage to look in the mirror and decide to exit gracefully. This can be the wisest decision, saving the team from unmanageable conflict and taking care of your own physical health because the amount of friction you will experience at every turn will be astronomical.

Founding Values and High Performing Teams

In our experience, one is far more likely to be able to put the rest of this practical guide to good use and far more likely to achieve high performing teamwork if the founding values have some clear map to Lencioni and Google’s work. In our experience, those values look something like this:

Your team’s founding values may use different words, you may put different priority or emphasis on certain words, and some words may span different parts of the High Performing Team pyramid — all of which is perfectly fine. What you want to be aware of and cautious about are core, founding values that work against the concepts embodied in High Performing teams.

For example, if “competition” is one of the most prized values for your founding team, so be it — but be highly aware that competition can often beget high ego and working against each other inside an organization, which is the opposite of what we want. If you have “red flag” values that show up, discuss them and develop a plan for how you will get the best of those values implemented while outlining a plan to eliminate the potential negative influences. Be aware, too, that one vocal member of a team may influence others to include values that work against High Performing team concepts — that may be a sign that the person should exit the team as opposed to a sign that your team should adopt that core value.

This topic will continue with Segment 3 — stay tuned.

Subscribe via email or RSS to get updates.

Footnotes

- Fermyon Values Agreement - the document that every employee at Fermyon signs, which document came as a result of the Values exercise in this segment.

- High Performing Startups — The Fermyon System (Segment 1)

- High Performing Startups — Segment 3 coming soon!

- The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick Lencioni (and the many other subsequent, excellent books by Patrick)

- Leaders Eat Last Simon Sinek